An Introduction to Chado

Chado, also known as chanoyu and commonly referred to as the Japanese Tea Ceremony in English, is a spiritual and aesthetic discipline for refinement of the self — known in Japanese as a “do,” a ‘way’. The word ‘chado’ means “the way of tea.

This way called chado centers on the activity of host and guest spending a mutually heartwarming time together over a bowl of matcha tea. The host aims to serve the guest an unforgettably satisfying bowl of tea, and the guest responds with thankfulness, both of them realizing that the time shared can never be repeated, that it is a “once in a lifetime” occasion.

The Spirit of Chado

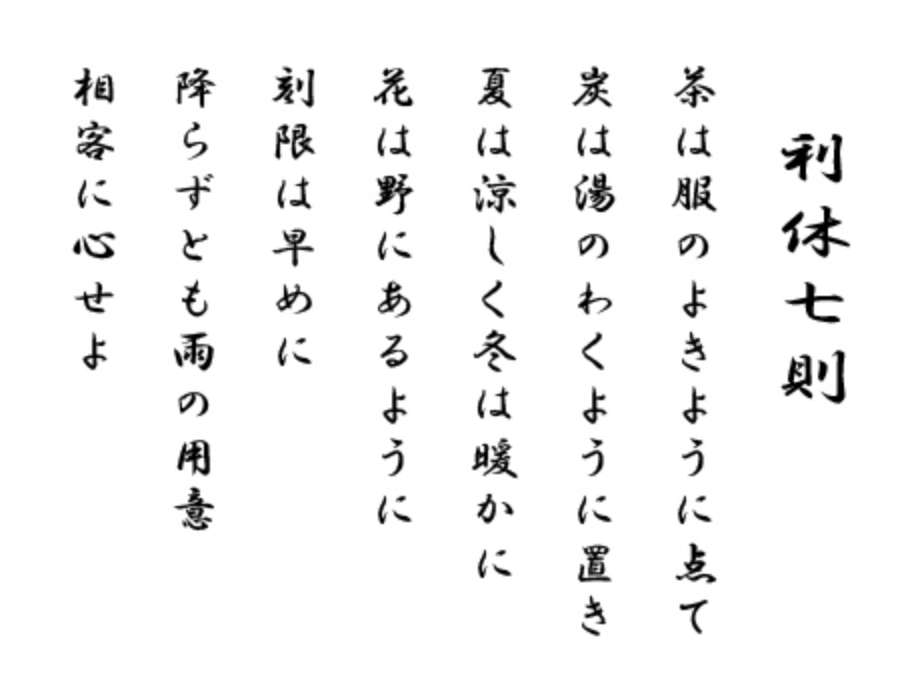

SEN Rikyu, the 16th-century tea master who perfected the Way of Tea, was once asked to explain what this Way entails. He replied that it was a matter of observing but seven rules: Make a satisfying bowl of tea; Lay the charcoal so that the water boils efficiently; Provide a sense of coolness in the summer and warmth in the winter; Arrange the flowers as though they were in the field; Be ready ahead of time; Be prepared in case it should rain; Act with utmost consideration toward your guests.

According to the well-known story relating the dialogue between Rikyu and the questioner mentioned above, the questioner was vexed by Rikyu’s reply, saying that those were simple matters that anyone could handle. To this, Rikyu responded that he would become a disciple of the person who could carry them out without fail.

This story tells us that the Way of Tea is basically concerned with activities that are a part of everyday life, yet to master these requires great cultivation. In this sense, the Way of Tea is well described as the Art of Living.

As seen within Rikyu’s seven rules, the Way of Tea concerns the creation of the proper setting for that moment of enjoyment of a perfect bowl of tea. Everything that goes into that serving of tea, even the quality of the air and the space where it is served, becomes a part of its flavor. The perfect tea must therefore capture the ‘flavor’ of the moment — the spirit of the season, of the occasion, of the time and the place. The event called chaji — that is, a full tea gathering — is where this takes place, and where the Way of Tea unfolds as an exquisite, singular moment in time shared by the participants.

The enduring allure of the Way of Tea is proof of its profound meaning for people — not only Japanese, but people of all cultures. Having been nurtured on Japanese soil, it represents the quintessence of Japanese aesthetics and culture. But, over and beyond this, people far and wide have discovered that life is beautified by this Way — by the spirit that guides its practice, as well as by the objects which express that spirit and are an integral part of its practice.

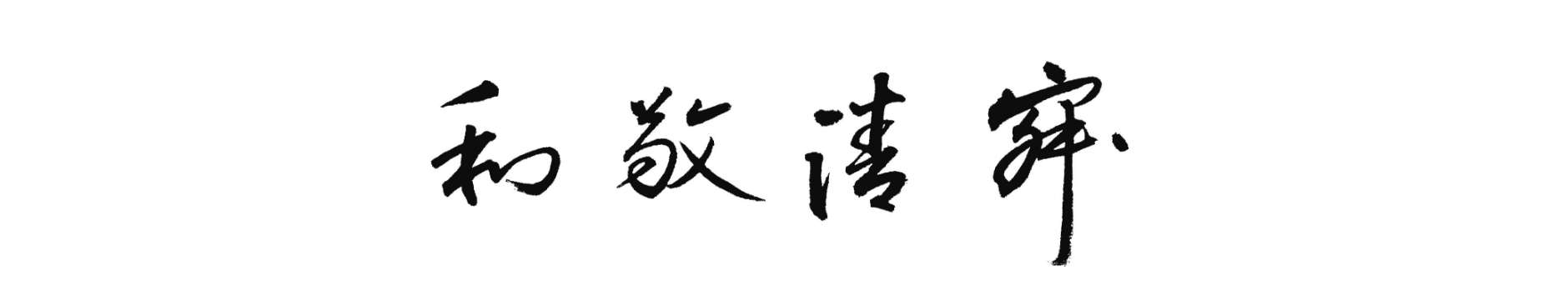

The principles underlying this Art of Living are Harmony, Respect, Purity, and Tranquility. These are universal principles that, in a world such as ours today, fraught with unrest, friction, self-centeredness, and other such social ailments, can guide us toward the realization of genuine peace.

Chado Origins and History

The tea plant probably originated in the mountainous region of southern Asia, and from there was brought to China. At first it was used as a medicine, but by the Tang dynasty (618-907), it came to be drunk mainly for the enjoyment of its flavor. Tea was so important that it was the subject of a three-volume work called Chajing, the Classic of Tea. At that time, tea leaves were pressed into brick form. To prepare tea, shavings were taken and mixed with various flavorings, such as ginger or salt, and boiled. Later, during the Song dynasty (1127-1280), green tea leaves were steamed, dried, and then ground into a powder. This powdered tea was mainly used for ceremonial purposes in temples, but was also appreciated for its taste by laymen.

Some tea was probably brought to Japan during the height of Japan’s first cultural contact with Tang China. Kukai, patriarch of the Shingon sect of Buddhism, brought tea in the brick form from China to the Japanese court in the early ninth century. Until the twelfth century, the drinking of tea in Japan was confined to the court aristocracy and Buddhist ceremonies.

Eisai (1141-1215), who introduced the Rinzai Zen tradition to Japan, introduced tea in powdered form to Japan upon his return from study in China. He also wrote a treatise called the Kissa Yojoki, which extolled the properties of tea in promoting both physical and spiritual health.

Eisai’s interest in tea was shared by his renowned disciple Dogen (1200-53), the patriarch of the Soto sect of Zen Buddhism in Japan. When Dogen returned from China in 1227, he brought with him many tea utensils, and gave instructions for tea ceremonies in the rules which he drew up for regulating daily life at Eiheiji, the temple founded by him in Fukui Prefecture.

Appreciation of tea did not remain confined to temples and the court. Its popularity spread among the warrior class. Tea gatherings of this era were often boisterous affairs that included contests in which participants identified various teas and prizes were offered to the winners. These were usually accompanied by linked-verse sessions, liberal consumption of alcoholic beverages, and gambling, along with ostentatious displays of expensive tea utensils imported from China. The flaunting of things Chinese was a fad among the warrior leaders, who went so far as to send their own special envoys to China to collect art objects.

Nonetheless, such gatherings contained elements which were refined into the tea gathering of today. For example, the banquet became the light meal that often precedes the drinking of tea, overindulgence in alcoholic beverages evolved into an exchange of a few small cups of it, gorgeous arrays of flowers and displays of painted screens were reduced to a simple arrangement of flowers and a single scroll hanging in the alcove.

The process of refinement of the procedures to make tea involved a complex interaction of various elements: the ceremonial tea of the temples; the extravagant social teas of the aristocracy; the rise, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, of a newly prosperous and influential merchant class; and the powerful personalities of three men — MURATA Juko, TAKENO Joo, and SEN Rikyu.

MURATA Juko (1422-1503) lived during the brilliant culture of the Muromachi period (1392-1573). Juko was from Nara and had probably participated in tea gatherings that included popular amusements such as bathing. It is said that he later came in contact with Noami, an artistic advisor of Shogun ASHIKAGA Yoshimasa who was versed in the procedures of tea as it was served in Kyoto. After this meeting he moved to Kyoto, entered the Buddhist priesthood, and studied Zen under the direction of the eccentric Zen master Ikkyu Sojun (1394-1481) from 1474 until the death of the latter. There is evidence that Ikkyu was acquainted to some extent with Chinese as well as Korean tea procedures, and it seems likely that he imparted what he knew to his pupil. Within the tea practiced by MURATA Juko was the awakening of the concept that tea went beyond entertainment, medicinal value, or temple ceremony; that the preparation and drinking of tea could be an expression of the Zen belief that every act of daily life is a potential act that can lead to enlightenment. This belief manifested itself in the development of a new aesthetic for the practice, an aesthetic which sought beauty in the imperfect and in the simple objects of everyday life. Juko once said that, more than a full moon shining brightly on a clear night, he would prefer to see a moon that was partially hidden by clouds. Likewise, Juko found beauty in Japanese utensils, which had been considered inferior to those from China. In a letter to one of his disciples, he wrote, “It is most important to seek as many admirable traits in Japanese objects as in Chinese.”

MURATA Juko’s concept of Tea was to be further developed by TAKENO Joo (1504-55), heir to an affluent leather business in the flourishing port city of Sakai. At twenty-four, he moved to Kyoto and studied poetry from the courtier and accomplished poet SANJONISHI Sanetaka. His interest in such a cultural pursuit is an indication that — like near contemporaries in Renaissance Italy — the wealthy merchants of Japan were interested in acquiring a broad culture. Since Sakai was a center for trade with China, its merchants were in a unique position to collect works of art, including tea utensils, from the continent. Joo broadened the practice of Tea. For example, he simplified the four-and-one-half-mat tearoom preferred by Juko by replacing the white-papered walls with unpapered earthen ones, by using lattice work of bamboo instead of fine wood, and by making the toko alcove narrower and framing it with natural wood. Though himself very wealthy, he disliked ostentation and preferred an unpretentious setting with simple utensils.

TAKENO Joo’s outstanding disciple was SEN Rikyu (1522-91), who was already accomplished in the art of Tea when at the age of nineteen he became a disciple of Joo. Rikyu, born in Sakai, was the eldest son of a wealthy merchant and warehouse owner. Records indicate that his grandfather, Sen’ami, was one of the artistic advisors to Shogun ASHIKAGA Yoshimasa but moved to Sakai to seek refuge from the Onin War which ravaged Kyoto. Although Rikyu’s family name was Tanaka, he used the name Sen from his grandfather. Rikyu began studying Zen at Nanshuji temple in Sakai under Takeno Joo’s Zen master, Dairin. The tea masters of Sakai were interested not only in the practice of Tea but in Zen as well. This may help to explain their espousing the aesthetic ideals of simplicity and understatement. Almost all of the great tea masters of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries studied Zen at Daitokuji temple, and the tradition continues even today.

Rikyu moved to Kyoto and continued to study Zen under Abbot Kokei at Daitokuji. His innovations in the practice of Tea incorporated the essence of his Zen experience. For example, many of his innovations did away with the discriminations which the ordinary mind makes: between man and nature, nobleman and commoner, priest and laity, beautiful and ugly, religious and secular. Thus, in his design of the tea hut and the path that leads to the hut, he sought to heighten awareness of man’s oneness with nature. By designing an entrance to the tea hut through which guests had to crawl regardless of rank, he sought to eliminate the social distinctions which separated human beings from each other. By finding beauty among common utensils, he sought to transcend the usual distinction between beautiful and ugly.

SEN Rikyu was not a recluse seeking escape from the world in the quiet of the tearoom. In Zen, quiet sitting and vigorous action are, after all, two aspects of the same thing; they are not contradictory. Through Rikyu’s association with the two great political figures ODA Nobunaga and TOYOTOMI Hideyoshi, he was often in the very center of the political struggles of the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1614). He first became tea master to Nobunaga, who emerged as the strongest of those competing for power after the decline of the Ashikaga shogunate. Whatever Nobunaga’s other interest in tea may have been, he certainly used it extensively for political purposes. Through his connection with Rikyu and other tea masters from Sakai, he was able to win the favor he needed in that city. On occasion he would reward those who had served him well by giving them celebrated tea utensils which he had collected. Sometimes he would give authorization for a General to conduct a tea gathering. This was considered an extraordinary honor. Among those given such permission was Hideyoshi.

Hideyoshi, after an important military victory in 1578, received permission from Nobunaga to serve tea. A record of a tea gathering at an earlier date mentions that Hideyoshi served tea to Rikyu. Nobunaga must have recognized Hideyoshi’s skill in the procedures to allow him to serve tea to Rikyu, for Rikyu was Nobunaga’s own tea master. After the death of Nobunaga in 1582, Hideyoshi took the reins of power and appointed Rikyu as his personal tea master. The following year, as part of his effort to win the political support of the people of Sakai, Hideyoshi invited important townsmen to a tea gathering at which Rikyu did the making of the tea.

Though Hideyoshi at times definitely enjoyed the flamboyant, he also appreciated the simple, spare style of Tea preferred by Rikyu. Hideyoshi’s grand castle in Osaka, a symbol of his new political power, contained not only the famous portable Golden Tearoom but also a small two-mat hut called Yamazato, “Mountain Village.” The Golden Tearoom was taken to the imperial palace in Kyoto in 1586, for a special tea to honor Emperor Ogimachi. Rikyu was Hideyoshi’s chief aide for this event that featured not only the Golden Tearoom but utensils of gold, as well.

Tea served in a golden tearoom is often criticized as being in direct contrast to the simple tea of a thatched hut. Such a contrast is particularly disturbing to Western minds which think of opposites as being different and mutually contradictory, instead of as two facets of the same reality. There is no record of Rikyu’s actual feelings about the two contrasting styles, but one may surmise that due to his Zen training he probably recognized that his preference for a Tea of quiet, subdued taste implied a relationship with its opposite.

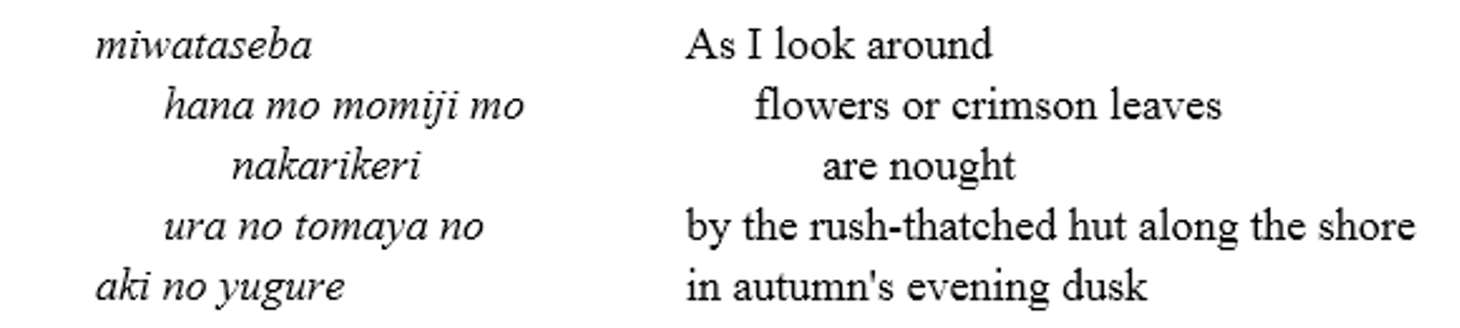

The relationship between the two kinds of Tea finds expression in this poem by FUJIWARA Teika (1162-1240), which was taught to Rikyu by his teacher, TAKENO Joo, as an example of the wabi spirit of tea:

For Joo, the flowers and colorful leaves could be compared to the tea practiced by those who craved luxuriance, while the simple hut on the shore represented the spirit of the wabi Tea that Joo was trying to practice. However, one could truly appreciate the wabi-style hut only after becoming saturated with the life of flowers and colorful leaves.

Though Hideyoshi seems to have leaned toward the extravagant, it is clear from records of various tea masters of that time that he was also capable of appreciating and participating in the austere service preferred by Rikyu.

After Rikyu’s death, his son-in-law, Shoan, inherited the family estate in Kyoto, and when Shoan retired, Rikyu’s grandson, Sotan, succeeded as head of the Sen family. When Sotan retired, he divided the property among his sons. The front part of the main estate was given to Koshin Sosa. Senso Soshitsu inherited the back part of the property. A house on Mushakoji street went to Ichio Soshu. From the tea practiced by these three sons, there arose the Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushakojisenke traditions of Tea, respectively.

Some of Rikyu’s disciples also formed their own lineages of Tea, and besides these, many other lines branched out in later periods from the Urasenke and Omotesenke lines. The various lines of Tea that existed during the Tokugawa era (Edo period; 1615-1868) emphasized and characterized the rigid class structure of the society of that era. There were those which lent themselves to the noble class; others, to the samurai class; and still others, the merchant class.

With the collapse of the feudal system, brought about by the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the hereditary successors to the Tea lineages lost much of their income. In this circumstance, the thirteenth generation Urasenke grand master, Ennosai (1872-1924), became acquainted with a circle of businessmen, who banded together to give support to Urasenke. The succeeding grand master, Tantansai (1893-1964), formed a national organization for Urasenke followers, and also began introducing the tradition of Tea abroad. His heir, Hounsai (1923-2025) , father of the present grand master, strived indefatigably to spread international appreciation of the Way of Tea, and through his dynamic efforts Urasenke has become the largest tradition of Chado both in Japan and around the world. Today, Zabosai SEN Soshitsu XVI, who on December 22, 2002, succeeded as the sixteenth-generation grand master in the Urasenke line descending directly from SEN Rikyu, continues the practice of his forefathers.