Konnichian

— The Urasenke Home

Konnichian — The Urasenke Home

Important Cultural Property and Historical Site (Not open to the public)

The Japanese Government designated the tea rooms and garden of Konnichian — said to be quite outstanding among the historic tea-culture related properties, and considered to represent the epitome of the rustic, thatched-hut style — a Historical Site in 1957 and an Important Cultural Property in March, 1976.

Kabutomon and the Roji walkway

Ōgenkan

Mushikiken

Koshikake

Roji

The Chūmon

The Yohobutsu-no-tsukubai

The Kosode-no-tsukubai

Yuin

Konnichian

Rikyu Onsodo

The Shaku-no-e-mado of Ryuseiken

Kan’untei

Totsutotsusai

Hogobusuma

Ume-no-i

Hosensai

Yushin

Tairyuken

Kabutomon “Helmet Gate” and the Roji “Dewy Path” walkway

The bark-roofed gate with bamboo guttering is thoroughly imbued with a wabi feeling. It was built during the Tempo era (1830-44) by Gengensai, the eleventh generation grand master. Seen from the garden side, the slightly curved sides and an arch-shaped cutout give the roof the appearance of a samurai helmet, hence the name Kabutomon, “helmet gate.”

A few steps inside the gate, a walkway of small paving stones, leading to the main entrance, angles off to the right through clipped hedges on both sides. As one proceeds down the walkway surrounded by dewy moss and luxuriant foliage, there is a sense of leaving the hustle and bustle of everyday life into a “mountain hermitage in the city (shichū no sankyo).”

Ōgenkan—Main Entrance Foyer

At the end of the walkway is the impressive main entrance to the tea room complex. Under a deep, bark-shingled eave, the paving stones give way to diamond-shaped tiles. A bamboo-floored landing extends across the width of the main section. A partial sleeve wall on the left side separates the main entranceway from a secondary entrance with its own stepping-up stone.

The right half of the main entranceway is in the formal shoin style with sliding wooden doors on either side of two shoji doors. The left half is in a less formal style with two shoji doors that slide past each other. The design elements convey unique expression and a sense of historic considerations of status and purpose.

Mushikiken “Shelter of Unchanging Color”

From the main entrance, a hallway leads back into the house to the Mushikiken, which functions as a waiting room (machiai). The original room is thought to have been built by Senso, but the present room is attributed to Fukensai, who had extensive changes made. The room’s name, “Shelter of Unchanging Color,” derives from the phrase “Pines throughtout time have unchanging color.” A wooden plaque with Chikuso’s calligraphy of this phrase hangs outside the room.

Two wide fusuma separate the main room of five tatami from an anteroom of three daime-size tatami. The wall at the right side of the guests’ area is papered and serves as the place to hang a scroll. A wooden-floored area the size of one tatami serves as a kind of toko alcove, where flowers are usually displayed. Formerly, this area served as a landing for a covered walkway which communicated to the Yanagi-no-ma anteroom of the Kan’untei. The sunken hearth (ro) is located in the right corner of the tatami where the host sits to prepare tea, above which is an attached shelf called Senso’s Kugibako-dana, “nail-box shelf.”

Waiting bench – Koshikake

The roji garden is entered from the Mushikiken. Against the garden wall is a sheltered waiting bench thought to have been designed by the fourth-generation grand master, Senso. It has a bark-shingled roof held down by a bamboo lattice and stones, a style of construction characteristic of the Kaga region where Senso frequently traveled. The stones in front of the bench indicate where the guests should sit. The Kinin-seki, “noble’s stone”, indicates the main guest’s seat.

Roji – “Dewy Path”

Because Urasenke has many tearooms, the layout of the paths through the garden and the placement of the stepping stones, seen from the waiting bench, appear very complex. The roji extends to the tea rooms in two parts. From the waiting bench, a stretch of “scattered hailstones” pavement leads to the middle gate. The atmosphere here is created by the shading of the evergreen trees and the light and shadow created by sunlight shining through. Even the presence of those passing through seem to slip from view.

The Chūmon middle gate

Because Urasenke has many tearooms, the layout of the paths through the garden and the placement of the stepping stones, seen from the waiting bench, appear very complex. The roji was skillfully laid out by Sotan with Konnichian and Yuin as the focal points. Beyond the stepping stones and a stretch of “scattered hailstones” pavement is the middle gate (chumon), with split-bamboo roof. Considered to embody Gengensai’s taste, it is a famous example of a light wabi-style gate.

The Yohobutsu-no-tsukubai

Along the way to the Yūin teahouse, there is a distinctive square tsukubai with Buddhist images carved in relief on the four sides, and is thus called the yohōbutsu no tsukubai. Nearby is a stone lantern which Kobori Enshū is said to have presented to Sōtan.

The Kosode-no-tsukubai

In front of the Kan’untei, there is Rikyū’s Kosode-no-tsukubai stone water-basin and Sōtan’s stone lantern. It is said that when Rikyu was about to be given a kosode garment by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he asked for a garden stone instead, and was given the stone in front of Kan’untei. The name may also come from the resemblance to the Rikyu-favored kosode shape.

Yuin “Re-Retirement Hut”

Even after constructing Konnichian, Sotan was involved in family matters. When the time came for his final retirement, he built a new retirement retreat, naming it “Yuin,” literally “again retiring.”

The dominant feature of the exterior of the teahouse is an imposing, rush-thatched, semi-gabled roof. The interior is of a conventional four-and-a-half-tatami layout, probably similar to Rikyu’s teahouse at his Jurakudai residence. A daime-size toko alcove is located on the north side, facing south. The toko post is Japanese cedar with knots on the bottom half. A utensil cabinet is built into the wall along the length of the tatami where the tea is made, which faces north. White paper wainscotting is pasted on the lower portion of the two walls bordering that tatami. The corner post has been plastered over to a height of one meter, and a hook for hanging a flower container is attached to the exposed section.

The “crawl-through doorway” (nijiriguchi) is located in the east corner of the south wall, and an exposed reed-lattice window is located diagonally above it. The only other window is located on the east side, in the wall behind the guests’ tatami. Both the south and east walls are covered with dark-blue paper wainscotting. The ceiling, of woven wooden slats with bamboo transverse pieces, is extremely low, only 1.75 meters from the floor. In the section of the ceiling which slants down to the south wall is a skylight, which can be pushed open through the thatched roof.

Yuin is considered an exemplary teahouse built according to the true principles of Tea.

Konnichian “Hut of This Day”

The tiny one-tatami-plus-daime room adjacent to the Kan’untei is the Konnichian, the tearoom whose name is synonymous with Urasenke.

The story of how the room got its name is well known. At the age of seventy-one, Sotan gave his son Koshin Sosa charge of Fushin’an and built a tearoom in the back garden as his retirement retreat. Upon its completion, Sotan invited his Zen master, the priest Seigan Soi, to a tea gathering. On the appointed day, Seigan failed to appear on time, and after waiting a while, Sotan went out. When Seigan finally arrived, he found Sotan’s message inviting him to come back the next day. Seigan scribbled his now-famous answer, “A negligent monk expects no tomorrow,” and went home.

Returning soon after, Sotan found the message and quickly grasped its meaning. Feeling shame for his insolence, he went to Daitokuji to apologize for his behavior that day. Later, he named the new tea room “Hut of This Day,” referring to the phrase Seigan had written.

The tea room represents the epitome of the thatched-hut style formulated by Rikyu. On the left side of the three-quarter size tatami (daime) where the tea is made is a built-in utensil cabinet, and on the far side is a wooden board inset. The fenestration of the outer wall features a small “poem card window” (shikishi mado) beneath a large window covered with two sliding shoji panels. A “crawl-through doorway” (nijiriguchi) is also located beneath this window at the south end of the one-tatami guests’ area. At the opposite end of the mat, a portion of the wall is set aside for hanging a scroll.

During a dawn tea gathering, the sunlight filtering through the trees strikes the shoji over the window in the east wall above the tatami where the host sits. The atmosphere created truly exemplifies Sotan’s wabi spirit.

Rikyu Onsodo, “Shrine of the Honorable Ancestor, Rikyu”

During the time of Gengensai, the Rikyu Onsodo Shrine was restored with funds donated by Lord KUJO Hisatada, and the wooden statue of Rikyu that had originally stood in the gate of Daitokuji temple was transferred here. A plaque written by Lord Kujo with the name Seijakuin, “Sanctuary of Tranquility,” hangs above the door.

Inside the shrine, the life-size statue of Rikyu stands behind a large round window at the back of an alcove. In front are a statue of Sotan in the seated position and a low altar table.

The main portion of the room comprises three tatami. A sunken hearth (ro) is cut in the board inset which separates the host’s and guests’ tatami. Senso’s suspended shelf, called the Hamaguri-dana, “clam-shaped shelf,” is at the far end of the host’s tatami. There is also a two-tatami anteroom which is used only on New Year’s Day and for traditional family rituals.

The Shaku-no-e-mado of Ryuseiken “Shelter of Restful Spirit”

The six-tatami Ryuseiken normally functions as the hall outside of the Kan’untei tea room. It is used as a tea room only on New Year’s Eve, to serve tea to guests who stop by to pay their respects. Afterwards, the charcoal remaining in the hearth is buried in the ash and left to smolder until morning. The embers are used to start the fire for the preparation of the Obukucha “Great Prosperity Tea,” which is offered before the statue of Rikyu. The water used for this tea is a mixture of water from the Ume-no-i “Plum Well” and water from the kettle which was left simmering on the hearth from the night before.

At the far end of the tatami where the tea is made, there is an exposed reed-lattice window. The handles of old bamboo ladles have been woven into the lattice. It is called the shaku-no-e-mado, the bamboo ladle window.

Kan’untei “Cold Cloud Arbor”

Because the wabi-style tea rooms Konnichian and Yuin were not appropriate for receiving members of the aristocracy, Sotan built a shoin-style room, Kan’untei. The room comprises eight tatami mats with a shoin window-shelf and an orthodox toko alcove. The painter KANO Tan’yu decorated the main room’s six fusuma panels with paintings of eight Chinese wizards. Next to the toko is a one-tatami space, called the Yanagi-no-ma, or “willow room.”

Although Sotan designed Kan’untei as a formal shoin, he imbued it with a wabi feeling through the unconventional use of architectural elements. For example, the room features a divided ceiling in three levels. The position of the sunken hearth (ro), in the right corner of the tatami where the tea is made, is also a feature conventionally used in rooms smaller than four-and-a-half tatami. Sotan also designed an arch-shaped transom inspired by a comb he received from Empress Tofukumon’in. Kan’untei is one of the most distinctive rooms in the compound because of its contrasting styles.

Totsutotsusai

Totsutotsusai is an eight-tatami tea room built by Gengensai in 1839 in commemoration of the 250th memorial for Sen Rikyu. It went through a mild remodeling in honor of the Sen Sotan 200th memorial in 1856, when it received its name, the Totsutotsusai, which was one of Sotan’s Buddhist names. The toko (alcove) pillar is a log from a five-needled pine that the eighth grand master, Yugensai, had planted at Daitokuji. The baseboard and lintel of the toko are made of ivy wood that Gengensai received from the Hisamatsu family of Iyo Matsuyama (present-day Shikoku). The ceiling is crafted of old pine planks from Daitokuji. These were mounted in alternating directions forming a pattern called ichi kuzushi, variations on the Chinese character for “one.” The auxiliary alcove features a large, exposed reed-lattice window. Totsutotsusai is used for the first tea gathering of the year (Hatsugama) and other Urasenke observances. The grand master also serves his personal guests here, and many royal visitors, world leaders, and other distinguished personages have been served tea in this room.

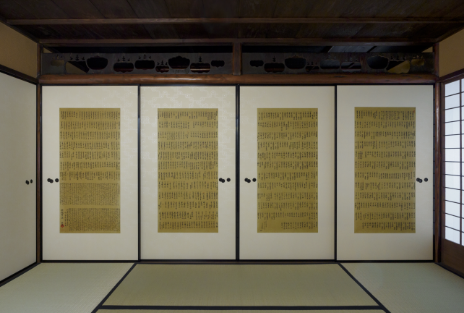

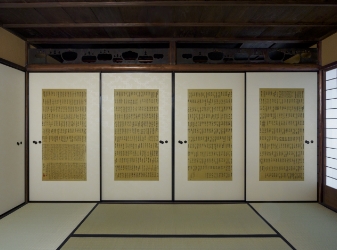

Hogobusuma

The anteroom of Totsutotsusai is called Tsugi-no-ma or Dairo-no-ma. It is a six-tatami room having a large sunken hearth (dairo) that is used only during the month of February. Four fusuma, called the Hogo-busuma, separate the Dairo-no-ma from the Totsutotsusai. Gengensai wrote a list of the major styles of tea making (temae) and the one hundred didactic poems attributed to Rikyu on the panels.

Ume-no-i “Plum Well”

The water of the Ume-no-i, “Plum Well,” has long been considered ideal for making tea. On New Year’s morning, using water drawn from this well, the grand master prepares Obukucha, “Great Prosperity Tea,” which is offered before the statue of Rikyu in the Onsodo.

Next to the Ume-no-i is a tall water-basin made of a unique stone which reveals chrysanthemum-shaped patterns on its cut interior. The stone was a gift from the Owari Matsudaira family.

Hosensai “Room of the Discarded Weir”

The Hosensai is a twelve-tatami room built by Gengensai. The name of the room comes from one of the names used by Rikyu. The room has a toko alcove wider than the length of a standard tatami. There is an auxiliary alcove having a built-in floor-level cabinet with sliding doors and a suspended shelf. In front of the toko alcove are two tatami with patterned edging which demarcate a special seating area reserved for members of the nobility.

The room is bordered on two sides by a veranda which opens onto the inner garden. The focus of the garden, which was laid out by Gengensai and renovated by Tantansai, is an aged red pine called the “Reclining Dragon.”

Yushin “Shelter of Newness Afresh”

To commemorate Tantansai’s sixtieth birthday, his wife, Kayoko, designed this tea room. The room is significant because it was the first built specifically to serve tea using benches and tables. The tile-floored main area is set with a specially designed table for preparing tea, and tables and benches for the guests. In the corner of the room is an L-shaped alcove with a lacquered shelf at the same level as the tabletops. The ceiling is made of old beams, smoked bamboo, and woven reeds, which convey a rustic feeling. Adjacent to the tile-floored area is a raised six-tatami room.

Tairyuken “Shelter Facing the Stream”

Ennosai built the fourteen-tatami room Tairyuken in 1923, the year in which his grandson, later the fifteenth-generation grand master, was born. The size of the room can be doubled by removing the shoji panels to incorporate the space of the surrounding corridors. The toko (alcove) pillar was made from a pine tree that grew outside the Yuin tea room. The cloth covering the doors of the cabinet in the auxiliary alcove was a gift from the aristocratic Kujo family. The altar curtain in the Rikyu Onsodo is also of this cloth. On the opposite end of the room there are four fusuma panels decorated with a scene of a stream flowing amid rocks and pines, by Maruyama Denne Roshi of Daitokuji temple.